Exploring the Mystery of Flushing

We had the opportunity to walk the streets of Flushing with Garnette Cadogan and Professor R. Scott Hanson this summer to explore “God’s Row-Bowne Street,” part of the “Nonstop Metropolis” exhibit at the Queens Museum.

Prof. Hanson is the author of City of Gods: Religious Freedom, Immigration, and Pluralism in Flushing, Queens recently published by Fordham University Press #Flushing #Queens #WorldsFair

Garnette Cadogan, excerpt from Nonstop Metropolis. A New York City Atlas, by Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Shapiro:

Love Your Crooked Neighbour / With Your Crooked Heart

How Flushing’s settlers planted seeds for our religious freedom

Get off the end of the 7 line—nicknamed “The International Express” because of the diverse ethnic neighborhoods this train traverses—and marvel at the bouquet that is Flushing, Queens. Step onto Main Street and see the poetry of movement on the sidewalks: the rapid passing of bodies that never bump, mimicking the choreography of industrious ants; person after person who walk from below the knees rather than from under the hips; and the shuffling pedestrian whose to-hell-with-you rhythm cuts through the flow of foot traffic as if protected by an invisible force field. Walk two blocks east past the bustle of Korean and Chinese and Indian and Bangladeshi shoppers, past the gourmands in from Manhattan on their culinary pilgrimages, struggling to orient themselves in the path of swift-moving passersby, past the bottlenecks that develop when customers spill out of restaurants and reflexology shops and reduce sidewalk traffic to little more than a single moving lane, until you reach placid Bowne Street. Here the wide sidewalks are sprinkled with unhurried residents. Walk north on Bowne Street another block and a half until you see a beige wood-framed house, with a sign on its lawn announcing:

Bowne House. built in 1661. a national shrine to religious freedom. …

Shortly after it was built, this house became a place of worship for Quakers, and therefore a place of refuge for them. Yes, spiritual refuge—“God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble,” as the Psalmist declared and the Quakers would wholeheartedly affirm—but also a shelter from harassment and persecution in the anti-Quaker climate of Flushing. Peter Stuyvesant, the director-general of what was then New Netherland—of which Flushing was a part—was not a fan of religions that weren’t his own Dutch Reformed. Observers of other faiths might pray and preach in private homes, but public homage was reserved for the national church of the Netherlands and New Netherland. …

His religious intolerance brought him into conflict with various newcomers to New Netherland who weren’t part of his tribe: Lutherans, Jews, Baptists, and others. But he had a special revulsion for Quakers, whose theological populism—their insistence that uneducated men and women could preach, for instance—and egalitarian style—their refusal to be deferential to ecclesiastical and political authority—he detested. …

In response to Stuyvesant’s ordinance, a group of thirty-one Flushing residents (only one of whom was a Quaker) got together and drew up a statement of protest. The Flushing Remonstrance called upon Stuyvesant to live up to New Netherland’s founding principles. Flushing was supposed to be tolerant of racial, ethnic, and religious differences. Like the colony’s namesake, the Netherlands, which recognized that “no one shall be persecuted or investigated because of his religion,” Flushing by its very charter was to allow residents “to have and enjoy the liberty of conscience, according to the custom and manner of Holland, without molestation or disturbance from any magistrate.” The signers of the Remonstrance not only stood up for other Christians, “whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker,” but they also insisted that “the law of love, peace and libertie” extended to “Jews, Turks and Egyptians.” …

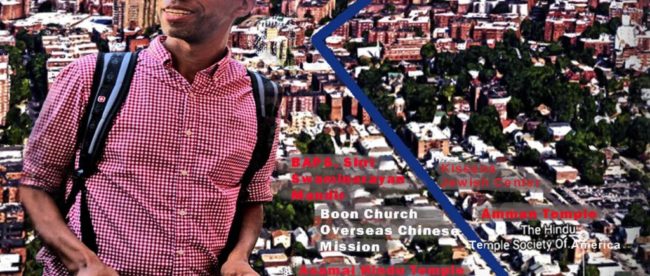

On the street in front of John Bowne’s house stands a signboard that lists other significant locations in Flushing. There are directions to Freedom Mile, a pair of self-directed walking tours within a mile’s radius of the marker; listed are places of historical significance (sites that might have been active in the Underground Railroad) and clues to a diverse present (the word Welcome in multiple languages). …

It’s on a street that’s one of the city’s “God’s Rows” (to borrow the term coined by journalist Tony Carnes, who has spent decades trying to map every religious site in New York City and has counted 372 in Flushing). Places of worship dot the street, as if sprinkled freehandedly from above. Walk on Northern Boulevard past the many spaces where Buddhists, Jews, and Christians of an array of denominations worship, and it’s easy to believe that this multifaith world is a creation of the Flushing Remonstrance. You’ll feel this even more when you walk a few blocks south of Bowne House past a Church of Christ, a Church of Oversea Chinese Mission, a synagogue, a Sikh Gurdwara, and a Hindu temple. …

Before us in Flushing were hurrying immigrant crowds, some of them from groups that are enemies in their home countries but have learned to coexist without rancor in these packed streets. There was none of the fear-born intemperance one saw, for example, in 2010, when Muslims wanted to build a mosque a few blocks from the World Trade Center site, where terrorists had left a scar in the city’s psyche. Some New Yorkers objected, stating that because the terrorists who committed that despicable act were Muslim, a mosque so close to Ground Zero was “insensitive.” Then-mayor Michael Bloomberg delivered a speech that rejected those claims, saying, “We would betray our values—and play into our enemies’ hands—if we were to treat Muslims differently than everyone else.” He invoked the Flushing Remonstrance, and declared: “Of all our precious freedoms, the most important may be the freedom to worship as we wish.” That document’s signers still summon us to stand up for others when we disagree with them; to recognize that our city thrives not only despite our differences but because of them; and to affirm, with W. H. Auden, that “You shall love your crooked neighbour / With your crooked heart.” It calls us, above all, to “doe unto all men as we desire all men should doe unto us, which is the true law of both Church and State.”

This excerpt is taken from Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas, edited by Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Shapiro, forthcoming from University of California Press, October 2016.

Exhibit “Nonstop Metropolis” at the Queens Museum, Flushing, Queens.

Another outstanding book on City of Gods: Religious Freedom, Immigration, and Pluralism in Flushing, Queens by R. Scott Hanson published by Fordham University Press in 2016.

To read more, visit A Journey Through NYC Religions.